Why you pitch poorly

We all pitch, even though most of us don’t use those words to describe the scenarios we find ourselves in. The word adequately describes what we do when we present a business case to gain approval for a service development or a new scanner. However, when we raise concerns that the currently proposed gimmick to save a few pounds is putting patients lives at risk, we tend to just say we are raising concerns. We are in fact, pitching, and arguably getting this one wrong is far more serious than another year without the latest clinical gizmo. They have something else in common too – we are pretty terrible at both! Given the importance of either to our future security and success, imagine how different life would be if we understood why we fail so frequently and how we might change that.

Defining Pitch

I am defining to pitch as the process of articulating a thought, idea, suggestion, business case or concern with the specific purpose of having someone react to it by doing something, either sensible or beneficial to us, or both. You may read that and think that I am simply describing influencing and that is partially true. However, whereas pitching is most definitely a part of influencing, influencing is not necessarily so easily or neatly folded into pitching because the act of pitching is generally an active ‘in the moment’ one, whereas influencing frequently takes place over time by undertaking a series of actions that don’t even necessarily involve the individual you are seeking to influence. So pitching is a present-focused activity demanding an immediate response.

If you want to explore the relationship a bit further, you could engage in an influencing strategy to improve the chances that your pitch is successful in the moment. If what you are pitching is important, I would advocate that as a very sensible approach. It may or may not be successful, depending on how good your influencing strategy is. However, the reasons why we fail at influencing are many and yet when it comes to pitching it boils down to one fundamental mistake, repeated time and time again. I would also suggest that the harder you think about an intelligent solution, the less likely you are to be successful.

The Mismatch of Species

I’d like you to imagine you genuinely have that safety concern and you wish to raise it with the project lead or a member of the senior management team. How do you approach it? You probably decide that if they are going to take it seriously, you need to think quite carefully about how to raise it and demonstrate that it is true. That leads you to pull out some data and sit in your office planning how best to articulate the concern you have. Having constructed a sensible, logical argument, based on some real data, you present the concern to the project manager and… BANG! What you thought was a barn door obvious safety concern appears to have been received as if it was a full blown personal attack (or with denial, or with irritation, or with anger). Familiar?

It goes on to turn out very badly. The defensive reaction produces a similar one in you, not helped by the sudden realisation in your mind that the safety of patients might just be in the hands of a lunatic. In truth, you got arguably what you programmed… by thinking, logically.

We fall into the trap of thinking that we must appeal to the logic centres of the brain and hence the tendency to carefully think through a logical argument. It is true that the argument must stack up too because at some point we are going to have to address the validity of the concern. The issue we face is that we don’t even get to that point if we start with the logical argument.

We fall into the trap of thinking that we must appeal to the logic centres of the brain and hence the tendency to carefully think through a logical argument. It is true that the argument must stack up too because at some point we are going to have to address the validity of the concern. The issue we face is that we don’t even get to that point if we start with the logical argument.

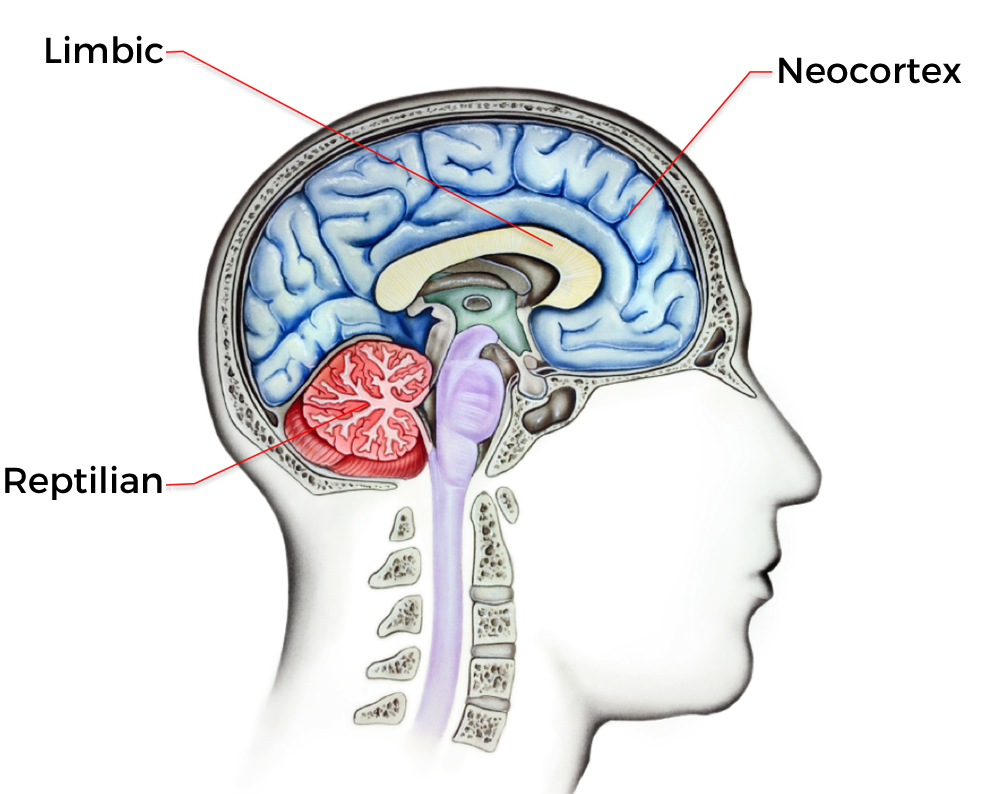

I don’t need to persuade you that our brains are highly evolved or that evolution takes a very long time. The challenge we face is that the bit of the brain scuppering our progress came into use before there was anything that even vaguely resembled a complex organisational, clinical and safety concern interacting with a set of financial circumstances. We are dealing with an issue to do with primitive processing. We pitched our concern to the highly evolved, deeply thinking neocortex and yet it never got near that in the person we pitched to. It came to a resounding stop at their reptilian gatekeeper.

This part of the brain is oldest, from an evolutionary standpoint, and it is the reason you and I remain today and in fact dominate the planet. We aren’t exactly the alpha species when it comes to physical prowess and with a 9-month gestation period, we couldn’t exactly reproduce faster than we could be eaten either. So, it had to be something else and this little centre, very close to spinal highway for passing instructions, is that something. It is there to answer perhaps three basic questions, being:

- Am I going to get eaten by it, or should I eat it?

- Should I mate with it?

- Is it interesting enough to explore further?

You can probably gather from this that there is a slight weakness in the computer programming when it comes to facing complex problems. You are trying to achieve the computing equivalent of decodifying the human genome on a BBC Micro (trainees – sadly, for the rest of us, you are too young to remember it but let’s just say it wasn’t that powerful). If we were asking Siri, or whatever your smartphone equivalent is, the conversation would go like this. “Siri, I have concerns that the current cost improvement project is going to lead to a degradation in patient safety. How should we approach it?”. Siri would probably answer “So, you want to know whether to eat it, or run like crazy in case it eats you?”.

Why the Aggressive Reaction?

I am sure you understand the basic nature of the problem. Anything and everything we raise with someone has to go through their Reptilian brain to gain access to their neocortex, even then passing through the limbic system, which won’t help at all. You can’t outsmart the croc because it doesn’t do smart. It does eat, run (rarely in the case of a croc), mate and perhaps explore, if it can be bothered. Explore is a tough pitch because it diverts attention away from eat, run and mate. Consequently, it has to be compelling. However, none of this explains quite why you drew such an aggressive response when you raised something that was genuinely in the interests of the Trust to understand and evaluate. Surely, disinterested would be more likely?

There is an answer and it is both simple and yet profound in its implications. The croc brain is there to keep an individual safe. Things fall into very few categories – safe, dangerous, desirable or uninteresting. Whereas you might feel, logically, that an individual is safer acknowledging a risk and doing something sensible about it, that’s a sophisticated thought process and certainly too subtle for the croc. The croc’s safety mechanism is based on immediacy – eat it now, run now etc. The particular croc you raised concerns with was leading a cost improvement project, in which success would reduce the Trust’s financial liability and the failure would put a blight on the career success and even job security of the individual. Therein lies the problem – you are the source of that threat and the most immediate, unavoidable threat sits firmly in an unignorable domain – their project. Faced with run, which is difficult when the project is your own, the reptile equivalent of abandoning your lair, or fight, you got the latter.

Is There An Answer?

The good news is that the problem is no more complicated than sending the wrong message to the wrong address. You sent a neocortex-packaged message to the croc brain. You can’t send anything to the neocortext without it going through this ‘portal’ and so the answer is don’t try. But… I hear you say, how then do I get through to the neocortex so that it can evaluate the risk? It’s a two stage process and at stage 1, it’s the croc that stands in the way. It’s best to think of it as a gatekeeper with a simple decision – is it safer and easier to keep you out, or safer and more desirable to let you in? The trick then is to get in through the front door. It’s then much easier to do what you need to do when you are on the inside.

If you want to understand this more, think about the difference between your boss saying to you that you handled a situation poorly versus the same message coming from your wife or husband. The first tends to be deeply distressing, especially when you start running scripts like “and I wonder how this affects what they think of me” and considering all manner of implications. But what are the implications of your wife thinking this? Is she going to fire you? Is she going to hold you back from a significant opportunity? No (well, I accept that I don’t know your wife or husband but I am guessing it’s no). Your croc brain has learned that there is little threat from your spouse on matters such as these and thus it might be an opinion you don’t want to hear but it isn’t an ‘eat it or be eaten’ scenario. Of course when my wife asks me if she looks OK in a new dress, my reptilian brain rings all sorts of alarm bells, as it has also learned that “you look lovely to me” is not a straight forward solution.

So, back to raising the concern. In crocodile speak, there are a few possible routes. You could say “Listen to the concern I am about to raise or I will eat you for breakfast”. Now, you’d have to be able to eat them for breakfast but assuming that was the case, the safer option for them would be to listen. However, in many cases, this will be a management-led project with a clinical concern, meaning the whole breakfast thing isn’t going to fly. In which case, we need a plan or approach B. We can’t appeal to ‘desire’ because there is nothing about this safety concern, in their project, that is going to appear in any way desirable or even intriguing (intrigue is, well, intriguing to the croc brain). We could go and find a bigger crocodile – a way of reintroducing the breakfast strategy but without you doing the eating. The issue is though that you are just as likely to be breakfast as them.

So, we are left with saving them from a threat that they didn’t know they had. It has to work in stages because it is working with that BBC Micro-level of processing power. It might sound a little like this “Bob, I think this project is a really great idea and we need the cost reduction. However, I am really concerned you are personally very vulnerable and really quite exposed. I am really busy right now but if you want to talk about it and what we might do, just make an appointment via my secretary. Must dash.” This associates risk with the project and additional risk because it is a.) personally orientated and b.) unknown (but present, in your opinion). The make an appointment component is important. It places you in a frame of ‘busy importance’ which suggests you are raising this for Bob’s own good. It also means that Bob is now chasing you i.e. you are the prize. Bob WILL make an appointment.

When he does, you can implement stage 2. This sounds a lot like “I really want to see you attain this cost improvement but not at the expense of a career-limiting safety issue. You’d probably never have spotted it (a personal safety ‘let off the hook’) because it’s complex. Let’s go through the issue, evaluate its likelihood and either come up with a sensible mitigation strategy or find an alternative way of creating the cost improvement.” You can probably see how at all stages you are managing the risk in the croc brain – safer to discover it, safer to evaluate it, safer to find an alternative, SAFER TO WORK WITH YOU than try to eat you. Consequently, you can now safely both deploy each of your neocortex’s problem solving ability together versus the threat. At the end, you’ll probably get “thanks for saving me from that one”.

Longer Term

This was just one scenario but an increasingly common one. As you can probably sense, the solution is genuinely simple – communicate at a croc level until it gives you access to the neocortex. However, knowing what to do and knowing how to do it are two different things and I am guessing you have already discovered that getting it wrong at a croc brain level comes with a fair bit of pain.

My encouragement is that in the complex and increasingly broken healthcare environment, anyone with a mind for safety and a role in leadership needs to understand this most basic and primitive of influencing components. The neuroscience has firmly caught up and what it’s starting to show is both fascinating and highly practical. It’s application isn’t just in raising concerns. As I said earlier, we pitch all the time in many different scenarios. But all of these scenarios have one thing in common. They all start at a croc brain level.